Brian Parker is a student at the Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands, enrolled on our MLitt Coastal and Maritime Societies and Cultures. A one-time nuclear physicist and later environmental scientist, on retirement he took an academic interest in history and obtained qualifications in local history and military history. The attractions of the current course, for him, are the Norse and Gaelic history of the Highlands and Islands, together with the archaeology of the Neolithic and, not least, the nature of ‘Islandness’, having lived on Anglesey for some years [David].

Brian Parker is a student at the Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands, enrolled on our MLitt Coastal and Maritime Societies and Cultures. A one-time nuclear physicist and later environmental scientist, on retirement he took an academic interest in history and obtained qualifications in local history and military history. The attractions of the current course, for him, are the Norse and Gaelic history of the Highlands and Islands, together with the archaeology of the Neolithic and, not least, the nature of ‘Islandness’, having lived on Anglesey for some years [David].

Those who walk coastal paths cannot help but be aware of geomorphological processes at the land-sea interface, particularly those of cliff and beach erosion, which tend to be both episodic and spectacular. Every winter some part of England’s South West Coast Path, for instance, has to be fenced off because of a cliff fall and a diversionary new route found. This is especially so on the Jurassic coast near Lyme Regis which has relatively frequent landslips after heavy rain. In this case, any instinct regretting the loss of land to the sea is more than offset by the cliff material being fossiliferous and each landslip is scoured by expert and amateur fossil hunters searching for the ultimate prize, a complete ichthyosaur.

The opposite of erosion, accretion, is usually less obvious to the viewer when it is year-on-year overall addition to the beach material. With beach accretion tending to be Darwinian in its change with time, it is often difficult for the casual observer to judge the extent and rate of that change without reference to old maps unless there are one or more markers to indicate where the tide line was at a particular time in the past.

Tentsmuir Forest at the north-eastern part of the Kingdom of Fife has beaches which are strongly accreting and there are also time markers in the form of WW2 concrete defences. The area was formerly sand dunes and moorland, acquired by the Forestry Commission in the 1920s as part of the urgent replanting programme following the exhaustion of timber supplies during WW1. The current owners are Forestry Commission Scotland. The north eastern tip of the area, outside the forestry plantations, is a National Nature Reserve, administered by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH).

The concrete defences of anti-tank blocks, with pill boxes at intervals, were installed in 1941 to deter possible German invasion from Norway. The SNH statement on the Reserve offers the view that the ‘line of anti-tank blocks has fortuitously provided a convenient reference marker for measuring coastal change’.[1] This is certainly so off the northern edge of the forest, at the mouth of the Firth of Tay, where the concrete blocks, sometimes referred to as ‘dragon’s teeth’, are exposed on the foreshore. Along the eastern side of the forest most of the blocks have disappeared under accreting sand, only occasionally visible where dune hollows have developed. An example can be seen in the first photograph, which shows an exposed pill box and concrete block. The pill box slit is facing seawards but well below the crest of the dune which continues to the right of the picture. About 10m from the pill box, the dune crest offers a prospect of the developing shore, as shown in the second photograph. The vegetated series of dunes in the middle distance form a newly developing ridge above high tide. The current shoreline on the far side of the ridge is 200m from the pillbox, which was at the shore line in 1941, representing about 2½ m accretion per year. In the nature reserve, even faster accretion rates are observed.

These anti-invasion defences are of interest to military historians. They were built by the Podhalan Brigade of the Polish Army, who, according to Lech Muszynski, the son of the Medical Officer in the Brigade, had arrived at Tentsmuir by the circuitous route of escape from Poland in 1939, being part of the expeditionary force at Narvik in 1940, transferred to France and being evacuated at Dunkirk.[2] This second hand oral reminiscence may not be entirely accurate, the time-table being extremely tight to include Dunkirk, but the survival of the unit to eventually arrive at Tentsmuir is indeed remarkable.

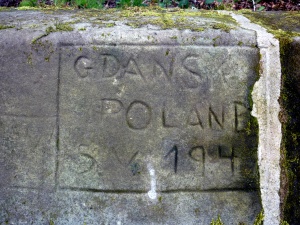

The Poles left traces of their time in the forest. On the track to a farm just before the entry gate to the forest is a bridge with sandstone walls. Wartime graffiti is evident in scratches on the stone, mostly too faint to interpret but one is more deeply inscribed and is legible, as shown in the photograph. It reads: ‘GDANSK/POLAND/S.V.1941’. This inscription is enigmatic; it is written in English and the letter ‘v’ is not part of the Polish alphabet.

The Poles left traces of their time in the forest. On the track to a farm just before the entry gate to the forest is a bridge with sandstone walls. Wartime graffiti is evident in scratches on the stone, mostly too faint to interpret but one is more deeply inscribed and is legible, as shown in the photograph. It reads: ‘GDANSK/POLAND/S.V.1941’. This inscription is enigmatic; it is written in English and the letter ‘v’ is not part of the Polish alphabet.

Not far from the inscribed bridge, deep in thick scrub of the forest, are remains of the Polish camp. Some of the brick walls of the central cookhouse building still stand, plus those of a covered well. The walls of the well are cement rendered and are inset with a finer coloured render in the form of a ‘heraldic’ shield. The markings on the shield are much decayed and not easy to interpret but the general features are discernible. The left panel of the shield has the crowned Polish eagle, facing outwards; the wing feathers are evident as also is the fearsome hooked beak. The right panel has the Scottish lion facing inwards. A feature of this, just visible in the photograph, are the long-extended claws. The lower panel shows the Scottish thistle. The artist who impressed these designs into the render clearly had talent. Further details about the camp and a marginally better photograph of the shield are available at Canmore.[3]

Not far from the inscribed bridge, deep in thick scrub of the forest, are remains of the Polish camp. Some of the brick walls of the central cookhouse building still stand, plus those of a covered well. The walls of the well are cement rendered and are inset with a finer coloured render in the form of a ‘heraldic’ shield. The markings on the shield are much decayed and not easy to interpret but the general features are discernible. The left panel of the shield has the crowned Polish eagle, facing outwards; the wing feathers are evident as also is the fearsome hooked beak. The right panel has the Scottish lion facing inwards. A feature of this, just visible in the photograph, are the long-extended claws. The lower panel shows the Scottish thistle. The artist who impressed these designs into the render clearly had talent. Further details about the camp and a marginally better photograph of the shield are available at Canmore.[3]

The Poles remained at Tentsmuir throughout the war, manning the defences they had put in place and carrying out other construction. One such was an observation tower facing into a bombing range at sea. It is possible to imagine nervousness on the part of the observers when an approaching aircraft delayed in dropping its bombs. The observation tower is now a holiday cottage.

The Poles remained at Tentsmuir throughout the war, manning the defences they had put in place and carrying out other construction. One such was an observation tower facing into a bombing range at sea. It is possible to imagine nervousness on the part of the observers when an approaching aircraft delayed in dropping its bombs. The observation tower is now a holiday cottage.

[1] Scottish Natural Heritage on-line at: http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/nnr/Tentsmuir_NNR_The_Reserve_Story.pdf.

[2] Lech Muszynski, The Polish Army Camp at Tentsmuir Forest, transcript of an oral history recording by Forest Heritage Scotland, available on-line at http://scotland.forestry.gov.uk/activities/heritage/world-war-two/world-war-tw-sites/tentsmuir-ww2-defences

[3] For further research on wartime Tentsmuir, see https://canmore.org.uk/site/141482/tentsmuir-forest

The photographs were taken by the author, who may be contacted at brianhenryparker@gmail.com.

.

I found this fascinating as I know Tentsmuir well. Do you know Robert Crawford’s recent book on the forest — I can’t recall its details but he has an unparalleled knowledge of the botany and has followed its geomorphological change for decades: there is also an older book , 1996, edited by Graeme Whittington, called Fragile Environments -the use and management of Tentsmuir. That is useful too

Chris Smout

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Chris,

Thanks for this. We’ll try and pass this comment on to Brian, the author of the post (from back in 2018) so he can respond.

Best wishes,

David

LikeLike

Here is Brian’s reply.

“Dear Professor,

Thank you indeed for the steer towards the geomorphological books on Tentsmuir. A most interesting area for a host of historical and landscape reasons. The accretion along the eastern side is quite marked. To find Polish wartime beach defences covered up well back in the forest was a surprise at first sight. The Forestry Commission is doing very nicely. Apart from planting P. sylvestris it can sit back and watch its acreage accumulate.

Best wishes

Brian Parker”

LikeLike