‘NASZ-DOM’. The letters on the house sign were startling. They looked Polish. In this context, ‘nasz dom’ meant ‘our home’.

Walking or driving around the north side of the outer Cromarty Firth always inspires or challenges me. But on this day in 2009, I’d set out to explore a Polish connection with Ankerville, in particular. Earlier in the afternoon, and looking westwards, I’d been reminded, additionally, of some wartime ‘sites of memory’ of a Polish nature to the west. And now there was this house sign. This coastscape was presenting me with reminder after reminder of a circular migration to and from Poland leading back to the 1600s.

Nigg is known today for the oil- and renewables-based activity associated with its firth-side yard. But the village and parish developed from a Pictish impetus. It remained a largely Gaelic-speaking community (like much of the rest of Easter Ross) until the twentieth century, and had, at times, a marked religious identity, as seen, for example, in the revival led by ‘The Men’ (Na Daoine) after 1739.

How did Nigg become also a key element of a transnational space linking Scotland and Poland in – as it seemed to me that 2009 day – an almost uncanny way?

Sometime in the 1720s, Alexander Ross – a merchant who had settled with a wife and two children in the Polish city of Cracow – made the decision to become a return migrant. By way of Scots Law, Ross received possession, in 1721, of the land and immovables of Easter Kindeace, just north of today’s Nigg village. Ross chose to rename his new Highland property ‘Ankerville’, an ‘anker’ being a measure of volume, dry or liquid, held in a barrel.[1] Subsequent accounts suggest that, metaphorically-speaking, any celebratory homecoming glass may have been half empty, tidal flooding being not the only fluid situation he had to deal with.[2] Richard Pococke, Anglican Bishop of Meath, travelled through the area later in the century, and was appalled by the story of Alexander’s life in Poland and his return. Influenced by an emerging, in part, pejorative stereotype, both of the Scottish Highlands and, in a very different way, Poland, Pococke’s account related that:

…we came to Ancherville, formerly the seat of one of the name of Ross, who from a very low beginning went into the service of Augustus of Poland… …and being the only person who could bear more liquor than his Majesty, got to be a Commissary, came away with the plunder of churches &c. in the war about the Crown of Poland, purchased this estate of £100 a year, built and lived too greatly for it, was for determining all things by the Sabre; and died much reduced in his finances between twenty and thirty years agoe.[3]

Pococke wasn’t the last to remember Ross’s return across the Baltic and North Sea. As late as the mid-nineteenth century, a local pointed out to the Cromarty-born writer, Hugh Miller, a ‘ghost story, that made some noise in its day; but it is now more than a century old’.[4] Its spectral subject was Ross, who the people of Nigg had come to know as the ‘Rich Polander’. Miller’s informant told him that:

…almost every evening, the apparition of the Polander, for years after his decease, walked along that road. It came invariably from the east, lingered long in front of the building, and then, gliding towards the west, disappeared in passing through the gateway. But no one had courage enough to meet with it, or address it.[5]

Other details of the ghost story had, by Miller’s time, long since been forgotten.

In nearby Invergordon, a Polish War Memorial survives today and is the location for an annual remembrance service for those who arrived in the Second World War to serve the allied cause, many of them settling in the area thereafter. For example, the late Józef ‘Joe’ Zawiński (1923-2011) found himself there as a survivor of the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, helped both to build the camp and, after the war, the monument. Much later, he assisted with organising and hosting the annual Invergordon service.

Perhaps it was one of those Polish ex-soldiers who had made a home so close to Ankerville at ‘Nasz-Dom’? The current residents aren’t sure and so I’d be delighted if any reader of this post could let me know.

As an historian who has written on Scotland and early modern Europe, I’ve been inspired by the likes of Murdoch, Grosjean, Mijers, Zickermann, and too many other leading lights to mention here (see Chapter Sixteen of this for the most recent overview). As regards Poland, I completed my PhD at Aberdeen, at a time when Dukes, Macinnes, and then Frost and Friedrich, were starting to give new energy to Scottish historical research on the theme. The recent works of, for example, Kowalski, Bajer, Kalinowska and Gmerek, have guided and informed my latest research, publication and commitment to online public engagement (alongside Joanna Kopaczyk of the University of Edinburgh) on how Scottish-Polish connections have been remembered.

I migrated to make my home further north in Easter Ross too. Because of that, I find that this evidence of the interaction of history and memory, of repeated to-and-fro travel across borders, puts our twenty-first century world’s fixation with national frontiers, and its frequent xenophobia, into context. Poles in Scotland today (have a look via the links that follow for evidence of some relevant heritage groups and activities) are making a full-blooded, profound contribution. They are presenting themselves – with depth and imagination – as part of an historical tie with this country going back centuries. An extraordinary example springs to mind. Through community workshops, a book, a Wojtek Memorial Trust and now an Edinburgh monument, a beer-drinking, cigarette-smoking brown bear has become a visible symbol of that Scottish-Polish history and, more broadly, of the triumph of humanity and hope in a time of adversity.

I’m fairly sure that there will never be a re-created ‘Sandy the Friendly Ghost’ to compete with Wojtek (or now, Baśka the polar bear) for people’s affections. It’s quite a weird thought to even consider. But the coastal and marine world that linked Bayfield, Nigg, with the Bay of Gdańsk and then inland via the Vistula, is a microcosm of that extraordinary connection via the North Sea and Baltic that we’re still learning about and that our students at the University of the Highlands and Islands are doing short courses on today. In its transnational complexity, it speaks of the historical and contemporary challenges of migration: mental health and language are two areas where exciting new projects are in place and further plans afoot, these having been the subject of discussion at a 2016 Inverness conference in which I played a small part. Second, it shows that, with a mix of adequate support from their hosts and determination, migrants can sometimes move on from tents, huts, sleeping bags on the beach, whatever their initial, bare shelter might be, towards finding that, one day, ‘our home’ becomes synonymous with their ‘dom‘.

Dr David Worthington, Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands

www.history.uhi.ac.uk

Some bodies and groups engaged in Scottish-Polish heritage and public engagement

Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Edinburgh: http://edinburgh.mfa.gov.pl/en/

Cross Party Group on Poland at the Scottish Parliament: http://www.parliament.scot/msps/poland.aspx

Scottish Polish Cultural Association: https://www.scotpoles.co.uk/

Polish Cultural Festival Association: https://www.pcfa.org.uk/

Polish-Scottish Heritage: http://polishscottishheritage.co.uk/

Bloody Foreigners: https://www.pcfa.org.uk/bloody-foreigners

Wojtek the Bear Workshops: https://www.pcfa.org.uk/wojtek-the-bear-workshops

Scottish-Polish Historical Links: https://www.facebook.com/ScotlandPoland/

Scottish-Polish Links (@ScottishPolish): https://twitter.com/scottishpolish

Migrants Matter: http://www.birchwoodhighland.org.uk/blog/2016/3/2/migrants-matter

Feniks: http://www.feniks.org.uk/

SSAMIS: http://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/gramnet/research/ssamis/

Linking Northern Communities: http://www.scottishinsight.ac.uk/Programmes/Programmes20142015/LinkingNorthernCommunities.aspx

The Great Polish Map of Scotland: http://www.mapascotland.org/

The Sikorski Polish Club: http://www.sikorskipolishclub.org.uk/

Fife Migrants Forum: https://www.facebook.com/fife.migrants/

Inverness Polish Association: http://www.polness.org.uk/

*Thanks to current ‘Nasz-Dom‘ residents, Graeme and Denise, for taking time to help me and for letting me take the photo of their house sign.

[1] Francis Nevile Reid, The Earls of Ross and their Descendants (Edinburgh, 1894), p.22; David Worthington, ‘“Men of Noe Credit”? Scottish Highlanders in Poland-Lithuania, c.1500-1800’ in T.M. Devine and David Hesse eds., Scotland and Poland: Historical Encounters, 1500-2010 (Edinburgh, 2011) pp. 91-108; David Worthington, ‘”Unfinished Work and Damaged Materials”: Historians and the Scots in the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania (1569-1795)’, Immigrants & Minorities, 20(10) (2015), pp.1-19.

[2] Marinell Ash, This Noble Harbour: A History of the Cromarty Firth (Bristol, 1991), pp.143-5.

[3] Cited in Nevile Reid, The Earls of Ross, p.22.

[4] Hugh Miller, Scenes and Legends from the North of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1869), pp.361-2.

[5] Ibid.

Brian Parker is a student at the Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands, enrolled on our MLitt Coastal and Maritime Societies and Cultures. A one-time nuclear physicist and later environmental scientist, on retirement he took an academic interest in history and obtained qualifications in local history and military history. The attractions of the current course, for him, are the Norse and Gaelic history of the Highlands and Islands, together with the archaeology of the Neolithic and, not least, the nature of ‘Islandness’, having lived on Anglesey for some years [David].

Brian Parker is a student at the Centre for History, University of the Highlands and Islands, enrolled on our MLitt Coastal and Maritime Societies and Cultures. A one-time nuclear physicist and later environmental scientist, on retirement he took an academic interest in history and obtained qualifications in local history and military history. The attractions of the current course, for him, are the Norse and Gaelic history of the Highlands and Islands, together with the archaeology of the Neolithic and, not least, the nature of ‘Islandness’, having lived on Anglesey for some years [David].

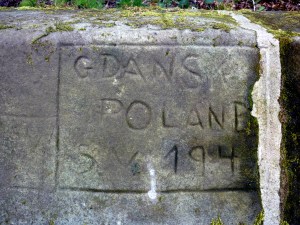

The Poles left traces of their time in the forest. On the track to a farm just before the entry gate to the forest is a bridge with sandstone walls. Wartime graffiti is evident in scratches on the stone, mostly too faint to interpret but one is more deeply inscribed and is legible, as shown in the photograph. It reads: ‘GDANSK/POLAND/S.V.1941’. This inscription is enigmatic; it is written in English and the letter ‘v’ is not part of the Polish alphabet.

The Poles left traces of their time in the forest. On the track to a farm just before the entry gate to the forest is a bridge with sandstone walls. Wartime graffiti is evident in scratches on the stone, mostly too faint to interpret but one is more deeply inscribed and is legible, as shown in the photograph. It reads: ‘GDANSK/POLAND/S.V.1941’. This inscription is enigmatic; it is written in English and the letter ‘v’ is not part of the Polish alphabet. Not far from the inscribed bridge, deep in thick scrub of the forest, are remains of the Polish camp. Some of the brick walls of the central cookhouse building still stand, plus those of a covered well. The walls of the well are cement rendered and are inset with a finer coloured render in the form of a ‘heraldic’ shield. The markings on the shield are much decayed and not easy to interpret but the general features are discernible. The left panel of the shield has the crowned Polish eagle, facing outwards; the wing feathers are evident as also is the fearsome hooked beak. The right panel has the Scottish lion facing inwards. A feature of this, just visible in the photograph, are the long-extended claws. The lower panel shows the Scottish thistle. The artist who impressed these designs into the render clearly had talent. Further details about the camp and a marginally better photograph of the shield are available at Canmore.

Not far from the inscribed bridge, deep in thick scrub of the forest, are remains of the Polish camp. Some of the brick walls of the central cookhouse building still stand, plus those of a covered well. The walls of the well are cement rendered and are inset with a finer coloured render in the form of a ‘heraldic’ shield. The markings on the shield are much decayed and not easy to interpret but the general features are discernible. The left panel of the shield has the crowned Polish eagle, facing outwards; the wing feathers are evident as also is the fearsome hooked beak. The right panel has the Scottish lion facing inwards. A feature of this, just visible in the photograph, are the long-extended claws. The lower panel shows the Scottish thistle. The artist who impressed these designs into the render clearly had talent. Further details about the camp and a marginally better photograph of the shield are available at Canmore. The Poles remained at Tentsmuir throughout the war, manning the defences they had put in place and carrying out other construction. One such was an observation tower facing into a bombing range at sea. It is possible to imagine nervousness on the part of the observers when an approaching aircraft delayed in dropping its bombs. The observation tower is now a holiday cottage.

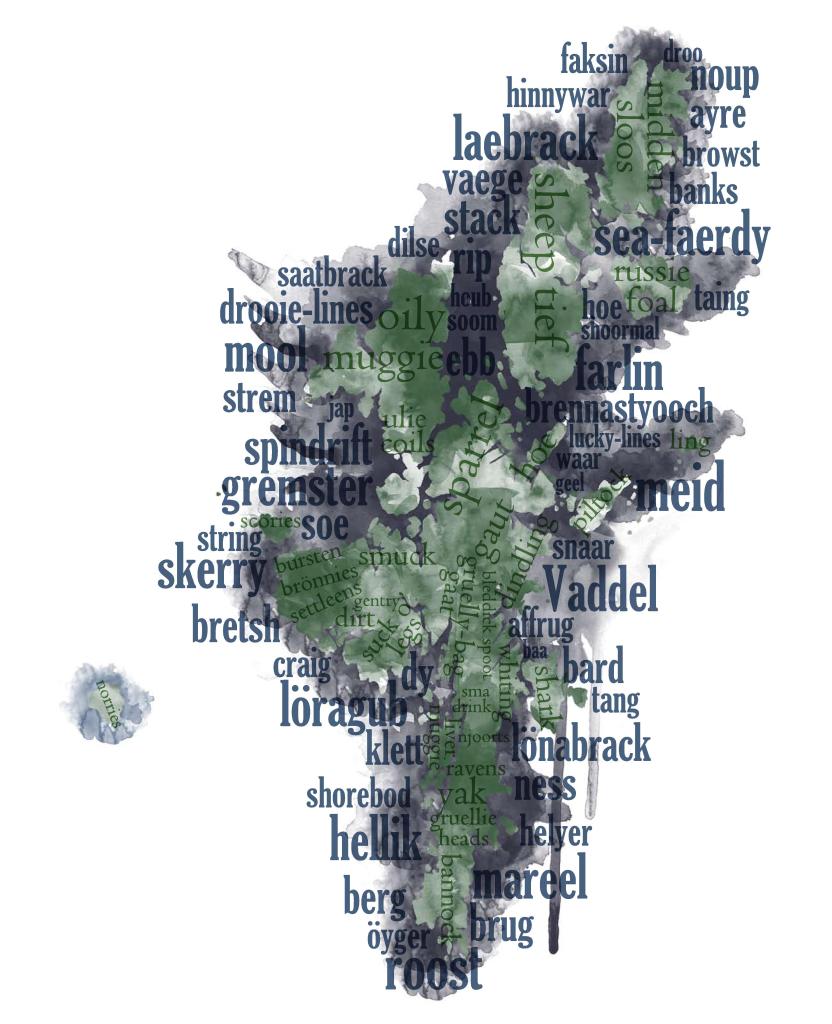

The Poles remained at Tentsmuir throughout the war, manning the defences they had put in place and carrying out other construction. One such was an observation tower facing into a bombing range at sea. It is possible to imagine nervousness on the part of the observers when an approaching aircraft delayed in dropping its bombs. The observation tower is now a holiday cottage. Our latest guest blog post is by Charlotte Slater. Charlotte was brought up and schooled in Orkney before heading to the mainland to study a BA (Hons) Landscape Architecture at Edinburgh College of Art. Having a keen interest in the marine environment, she transferred the skills and knowledge gained at university and became a Marine Spatial Planning Officer, based at the NAFC Marine Centre, Shetland.

Our latest guest blog post is by Charlotte Slater. Charlotte was brought up and schooled in Orkney before heading to the mainland to study a BA (Hons) Landscape Architecture at Edinburgh College of Art. Having a keen interest in the marine environment, she transferred the skills and knowledge gained at university and became a Marine Spatial Planning Officer, based at the NAFC Marine Centre, Shetland.